The Adaptive Functions of Dreaming: Theoretical Perspectives and Research Evidence

Introduction

Dreams have fascinated humans for centuries and have profoundly influenced beliefs and myths. We experience dreams during sleep and they comprise of range of experiences from fun and romantic to disturbing and bizarre. Dreams have puzzled humanity, as it remains unclear whether they hold any specific meaning or purpose.

Historically, people have analyzed dreams and attempted to interpret dreams to uncover their significance. Ancient civilizations believed divine figures communicated to human beings through dreams, and these dreams were interpreted to obtain meanings in the form of guidance or prophecies. Popular historical figures, such as Alexander the Great, reportedly relied on dreams to strategize the timing of his conquests.

However, the scientific community remains divided on the reliability and significance of dreams. Some theorists suggest that dreams serve as a form of “overnight therapy” playing a vital role in memory consolidation and emotional regulation (Pal, 2020). This essay explores various theories about dreams proposed by researchers, the adaptive role of dreaming, and their contributions to human survival and emotional well-being.

Freudian Dream Theory

Sigmund Freud was one of the first popular psychoanalysts to suggest that dreams could have a significant meaning in scientific research. He believed that dreams serve as a window to the unconscious mind, where our repressed unconscious desires, which cannot be acted upon in real life, would manifest through dreams. The American Psychoanalytic Association states that dreams express a person’s secret wishes and desires that could not be fulfilled in everyday life and depict emotions such as anger, trauma, and guilt. According to Freud, our dreams are influenced by our emotional states and the representations we make of them in our minds.

He argued that the primary driver of human beings is survival, and therefore, physical arousals that bring pleasure or discomfort affect our mental state. He believed that feelings depict our inner state of being, guiding individuals to adjust their behaviors to maintain homeostasis, meaning keeping our bodies healthy and balanced (Koslowski, 2023). Therefore, according to Freud’s psychoanalytic theories, dreams express the unconscious by allowing the mind to symbolically represent the repressed wishes of the unconscious. Freud sought to analyze the contents of dreams and how these elements work together. He referred to dreams as the “royal road to the unconsciousness” and proposed that the materials or contents of a dream are influenced by external stimuli, meaning changes happening within the body, and mental activities occurring during sleep.

Freud labeled the actual images or events we observe in dreams as “manifest content”, however, he argued that “manifest content” is how our minds represent the hidden wishes and desires of the unconscious, therefore, he sought to analyze these manifested contents to uncover the hidden meaning of the dream, which he dubbed as “latent content”.

Therefore, according to Freudian dream theory, dreams have a meaning, which would allow psychologists to identify and interpret the hidden wishes of the unconscious.

Freud also proposed that dreams assist in resolving unconscious conflicts, allowing individuals to experience emotional stress in a less intense “anesthetized” manner. This idea is supported by Walker and van der Helm’s analysis of REM sleep. They suggested that the emotional tone of the memories is desensitized, allowing individuals to replay these memories in a less potent manner. The vivid nature of dreaming stimulates emotional responses that may relate to unresolved unconscious conflicts in a person's mind.

Brain regions that are highly active during REM sleep include hippocampus and amygdala, which are involved in functions such as memory and emotion processing (Payne & Nadel, 2004). Dreams display contents that provoke an emotional response; hence it is natural that individuals feel a high level of emotional involvement whilst experiencing dreams. Certain conflicts that bring about feelings of anxiety and fear can manifest themselves to a greater degree than they do in waking life. This is demonstrated by the activation of limbic structures such as the Amygdala. These studies support Freud’s theories that dreams manifest threats and conflicts that an individual may be experiencing in their waking life.

Discovery of REM sleep

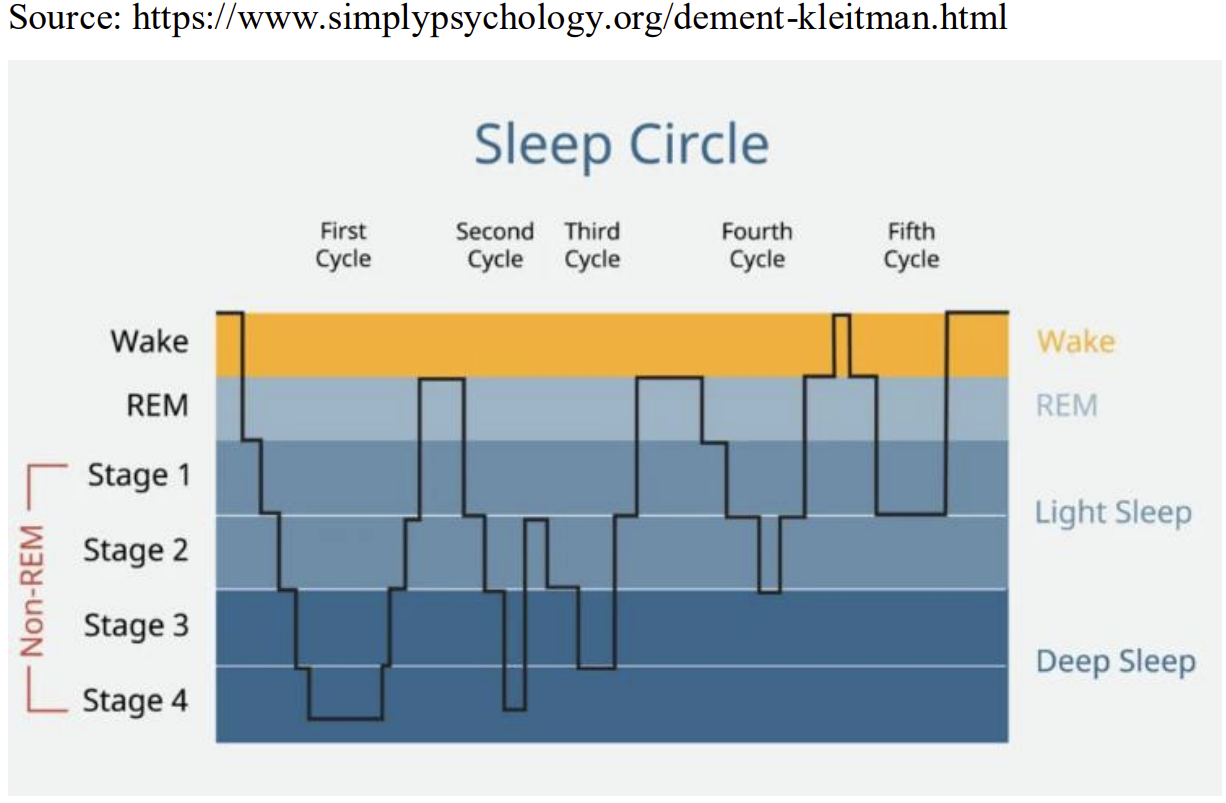

Most dreams occur during a stage known as the Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep. During REM sleep, a person's eyes move back and forth rapidly behind the closed lids, while their muscles remain paralyzed to prevent them from acting out the dream. REM sleep is considered a “wakeful” state compared to non-REM sleep as it involves more brain activity.

REM sleep was discovered by Aserinsky and Kleitman in 1953 (Zhang, 2005), although the origin of the term “REM sleep” is claimed to have been coined by William Dement, a medical student at Kleitman’s laboratory. Aserinsky, Kleitman and Dement used electrophysiological techniques to distinguish REM sleep in adults. In their 1957 paper, Kleitment and Dement identified five distinct sleep stages by examining the electrical activity of the brain. The participants who were awakened during REM sleep reported experiencing vivid visual dreams, in contrast to those awakened during non-REM sleep, who generally did not recall vivid dreams. Kleitman and Dement, observed the cyclical nature of REM and non-REM sleep, occurring every ninety minutes throughout the night. Further, a Russian study done in 1926, used pneumography to measure the breath and visual movements of infants. The study found that infants exhibited irregular body movements every fifty minutes, depicted by heightened heartbeats, side-to-side and downward eye movements, and irregular breathing patterns (Silber, 2023).

The Activation Synthesis Hypothesis

Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley introduced the Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis in 1977, a model that explains the formation of dreams. It states that during REM sleep the brain receives random electrical signals from the brain stem, which activate the regions of the brain that are responsible for vision and movement. These signals are then compiled by the forebrain to produce dreams. Hobson and McCarley described this process as the brain "doing its best to create a somewhat meaningful dream from chaotic inputs." This model was researched on animals, such as cats, who appear to generate similar brain waves. Yet, this model does not explain why images are dreamt owing to the electrical impulses in the first place.

However, Mark Solms, later argued that dreaming can occur without REM sleep, disputing Hobson and McCarley’s claim that dreaming is closely linked to the Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis model (Zhang, 2005). Furthermore, “Activation Synthesis Hypothesis” also suggest that dreams integrate recent experiences, facilitating learning and problem solving. For example, participants who engaged in maze navigation performed better after REM sleep, as the brain consolidates the memory (Stickgold and Walker, 2004). Further, if an individual has dreamt about a challenging task, they are more likely to perform it better when they are awake (Wamsley et al. 2010). Therefore, this demonstrates that dreaming assists in assimilating and harmonizing information to develop solutions for cognitive problems.

Moreover, in dreams individuals are presented with challenging or threatening situations which allow the dreamer to try out responses for threatening situations which is helpful for survival when encountering similar challenges in the real world. This hypothesis is dubbed as the Threat Simulation theory (Revonsuo, 2000). Revonsuo discovered that a large portion of dream activity revolves around situations where the dreamer is attacked or chased, which depicts our ancestral drives to survive and propagate in the real world.

According to Zadra & Donderi (2000), children who experience recurring nightmares demonstrate better threat management skills in real life. Hence, dreaming revives our survival capabilities allowing individuals to adapt to real-world threats. Dreaming is a topic that is discussed profoundly in mental health. Individuals who are undergoing mental health conditions usually experience recurring nightmares. This could be linked to anxiety and trauma or phobias which trigger these dreams and mental health symptoms. Patients who have PTSD experience recurring flashbacks of the traumatic event during their dreams, which disrupts the quality of their sleep and activities in day-to-day life. Although it was mentioned earlier that dreams act as a desensitizer for real-life stressors, it could also work the other way around if the dreams comprise persistent nightmares which worsens the individual's distress (Levin & Nielsen, 2007). Lucid dreaming is considered a therapeutic tool for treating certain psychological complications. Lucid dreaming is conscious awareness during dreams, where the dreamer is aware that they are experiencing a dream and can control the contents of the dream.

According to a study done by Holzinger et al, it was observed that interventions for PTSD-induced nightmares using Lucid dreams did not have any impact on the severity or frequency of the nightmares, yet the level of anxiety and depression experienced by the patient declined during the course of therapy.

In conclusion, the theories discussed above emphasize the adaptive functionalities of dreaming, demonstrated through Freud’s psychoanalytic approach, Threat simulation, and Activation Synthesis theories. The theories explored above, particularly Freud’s, intervene in the concept of dreaming with emotional regulation and resolving unconscious conflicts in line with Freud’s theories on exploring the unconscious mind. Whereas, the latter highlights the importance of dreaming for cognition and survival. Although dreaming may help individuals process stress and painful emotions, the recurring nightmares linked to mental health complications such as PTSD demonstrate that dreams could also cause distress. Hence, dreaming is an intriguing phenomenon that posits multiple adaptive functions ranging from emotional regulation to cognitive resilience, highlighting the interchanges between sleep, survival, and mental health.

References

Dement, W., & Kleitman, N. (1957). The relation of eye movements during sleep to dream activity: An objective method for the study of dreaming. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 53(5), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048189

Holzinger, B., Saletu, B., & Klösch, G. (2020). Cognitions in sleep: Lucid dreaming as an intervention for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2110. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02110

Koslowski, M., de Haas, M.-P., & Fischmann, T. (2023). Converging theories on dreaming: Between Freud, predictive processing, and psychedelic research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, Article 1080177. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1080177

Levin, R., & Nielsen, T. A. (2007). Nightmares and post-traumatic stress disorder: A review of the literature. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(2), 163-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.02.010

Nir, Y., & Tononi, G. (2010). Dreaming and the brain: From phenomenology to neurophysiology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.12.001

Pal, K. (2020). Theories of dreams and their role in emotional regulation. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Science, 12(3), 78-8

Payne, J. D., & Nadel, L. (2004). Sleep and memory: The role of sleep in memory consolidation. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 8(2), 93-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.002

Revonsuo, A. (2000). The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(6), 877-901. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00003976

Silber, M. H. (2023). Sleep disorders in children and infants: Current research trends. Journal of Sleep Research, 32(2), 145-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.13467

Stickgold, R., & Walker, M. P. (2004). Sleep-dependent memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 8(2), 149-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2003.10.004

Tuominen, J., et al. (2020). Dreaming as a training ground for real-life scenarios: Insights from predictive processing models. Consciousness and Cognition, 79, 102835

Vandekerckhove, M., & Wang, Y.-L. (2017). Emotion, emotion regulation, and sleep: An intimate relationship. AIMS Neuroscience, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2018.1.1

Wamsley, E. J., Shinn, A. K., & Tucker, M. A. (2010). The influence of REM sleep on cognitive performance. Nature Neuroscience, 13(2), 274-279. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2482

Zadra, A., & Donderi, D. C. (2000). Nightmare frequency and personality traits in a university student population. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(1), 153-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00138-9

Zhang, W., & Guo, B. (2018). Freud's dream interpretation: A different perspective based on the self-organization theory of dreaming. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 1553. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01553

Zhang, J. (2005). Continual-Activation Theory of Dreaming. Dynamical Psychology, 18(3), 203- 210.